[easyazon-image align=”left” asin=”B00CYI4KK2″ locale=”us” height=”160″ src=”http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51ilmi1oZsL._SL160_.jpg” width=”108″]The Story of Luke deals with a young man with autism, abandoned in infancy by his mother and raised by his grandparents. His grandmother, as his primary caregiver, had perhaps sheltered him more than she should have. Luke gets home schooled and/or takes distance learning classes for high school. He lacks vocational training or any sort of transition plan. When his grandmother dies, he is forced to move in with his Uncle Paul and Aunt Cindy, who have issues of their own (she’s on antidepressants, and he’s just a pill), and two younger (presumably) “normal” children. There are some scenes where “what to do about Luke” is discussed among others, and he overhears. Aunt Cindy has delicate sensibilities, and must have deep pockets as well, because she has the grandfather admitted to a nursing home following an incident where he attempts to grab her posterior, and offers her $20. At a rest stop on the way to the nursing home, Luke’s grandfather tells him that Luke is now a man and must live his own life, including getting a job and finding a woman who “is willing to travel and doesn’t nag too much”. At the rest stop, Luke meets a sympathetic convenience store clerk who gives him a pile of pornographic magazines when he asks about “screwing”. Luke’s final conversation with his grandfather has a strong impact on the boy, who decides, despite the challenges faced by his condition, to try to get a job and a girlfriend. These pursuits are made more challenging than they had to be by the fact that he lacks transportation, and his aunt is initially against him attempting to get a job. She comes around, when she realizes that enforced idleness and lacking the opportunity to acquire an adult role could be harmful and depressing to him as well.

Luke is not the “stereotypical autistic”. He speaks and responds to others, though stilted delivery and the repetition of common sayings act as an indicator that he does not have the spontaneity that others do, and the clearly-shown anxiety with every challenging situation he encounters hints at what lies beneath the polite well-groomed young man’s attempt at maintaining a socially-appropriate mien. He walks down the street covering his ears when loud sounds overwhelm him, and significantly sits in the seats reserved for the handicapped when he takes the bus. Some situations provoke a bit of mild “stimming”. Though he discloses some talent at preparing dishes he had seen made on cooking shows on TV, he denies any specialized or savant skills. When asked about his condition, though some call him “a retard” or say he has autism, he claims “my grandmother told me that I defy clinical categorization”.

The grandfather, who seems physically healthy other than an incident of incontinence and the revival of a smoking habit, dies conveniently the next time Luke is given the opportunity to visit the nursing home.

After he settles in with his aunt and uncle, Luke at first unsuccessfully pursues both work and love, signing up with a temp agency where he meets an older black woman “with nice tits”, who works as the receptionist, and is later the first woman he asks for a date. He finds out about a company that could help him, with a program called the Smile, which hires and trains people on the autistic spectrum for menial jobs within corporations. The owner, in fact, has an autistic son who works for him, Zack, supervisor of the new apprentices. Zack is bitter and abrasive, and feels a need to prove himself to his father. Luke is then hired as an apprentice and in spite of Zack yelling at him and being less than clear about some of his initial job responsibilities, he proves himself able to adapt. His resourcefulness and desire to ask out the girl at the temp agency hits Zack, who decides to try to help him, which has the result of helping himself at the same time.

Zack teaches Luke to carefully observe and mimic the body language and non-verbal interactions of “NTs”, or “neurotypical” people, and then shows him simulator software he developed which has on-screen virtual faces and personas responding in real time to Luke’s interactions with them. In spite of this unique training tool for human interaction, Luke still gets rejected when he asks the woman on a date. Zack ends up getting it used for customer service within the company, and hopefully, redeeming himself in his father’s eyes. Luke starts looking exceptionally personable and capable, and lands a long term job with the company.

In the meantime, Luke’s aunt, uncle, and cousins have been warming up to him, and discover the whereabouts of his mother. Zack helps groom Luke for the occasion and accompanies him when he decides to meet his mother. Luke discovers that his mother has another grown son and a family who doesn’t know about Luke, and she would prefer to keep it that way. Though Luke is disappointed that his reunion with his mother wasn’t a happy and loving one, by NT standards, he does get closure on why she acted as she did: “I didn’t think I would ever hear you talk to me” she said.

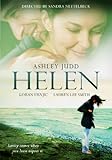

Helen

Helen starts out as a seemingly happy, successful college professor with a teenage daughter, a second marriage, and a spacious house and a car. The onset of Helen’s major depression comes slowly, almost imperceptibly, as she sits brooding in the dark and tells her husband “it’s nothing”. It only starts to become more obvious that she has a combination plate of depression and anxiety when she has a seemingly unprovoked panic attack when returning student essays in class.

Helen starts out as a seemingly happy, successful college professor with a teenage daughter, a second marriage, and a spacious house and a car. The onset of Helen’s major depression comes slowly, almost imperceptibly, as she sits brooding in the dark and tells her husband “it’s nothing”. It only starts to become more obvious that she has a combination plate of depression and anxiety when she has a seemingly unprovoked panic attack when returning student essays in class.

The true depth of Helen’s problem only becomes apparent when her husband finds her curled in front of the clothes dryer in a fetal position. When he brings her to the hospital, the doctor sends them to a neurologist, who goes through the depression inventory as Helen sits sullenly, and her husband initially answers the questions. To his surprise, her husband discovers that she has made a previous trip there 12 years ago, several years before they married. He expressed amazement that he had missed seeing the serious nature of her condition for so long. The neurologist told him; “some people hide it very well. You should see some of the clowns we have on suicide watch”. He prescribes an antidepressant and Ativan for the anxiety.

Meanwhile, one of her music students is experiencing a similar, albeit more dramatic, downward spiral into clinical depression. The movie intercuts to show the parallel track they take as their conditions increasingly impair their peace of mind and ability to function in society.

(I love the scene where Mathilda bangs her head against a glass partition in the hospital and cracks it. The The image very plainly portrays the collective frustration of any number of people with the medical and mental health systems as they exist in America today.)

When Helen’s medication seemingly fails to work and she makes a suicide attempt, her husband goes to the psych ward for help, and gets a different doctor who says she will change Helen’s medication, but will not hospitalize Helen against her will. Her husband is clearly frustrated, as Helen has made more suicide attempts, and he feels he can’t watch her constantly; to him, her need to be hospitalized seems obvious. This is not the case for the doctors who are not living with Helen, and who cite mental health laws as being meant “to protect people like her”, in this instance, by not society having people committed at the drop of a hat.

Meanwhile Helen grows worse, and her teenage daughter eventually ends up leaving her home to move in temporarily with her biological father (who has conveniently been waiting in the wings)

It is only after Helen experiences another non-lethal mental health crisis (she has taken too many Valium and won’t wake up) that the powers-that-be allow her husband to have her committed involuntarily.

It is then that Helen wakes up in the hospital. Helen and Mathilda meet as fellow psych ward patients and become friends and peers in a way that they probably would not have, had they remained teacher and student.

Of the two, Mathilda is the more damaged, and she is not only damaged by depression herself, but also indirectly. Her mother committed suicide and left her a house (a nice, clean beach house with giant picture windows) all ready for her and Helen to move in. Somehow, they seem to have enough money for groceries and utilities, even though neither of them have jobs, or were seen to file for disability benefits (I wonder how many of the mentally ill have prime beachfront real estate?).

Helen initially panicked at ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) being suggested for her, and argues when the doctor tries to talk her husband into consenting to ECT for her, but later, after her release from the hospital, chooses ECT of her own volition when she comes to the belief that by making the choice to have ECT, she is actively choosing the state of sanity. “Modern ECT” complete with general anaesthesia, an oxygen mask, and more, is depicted. The ECT experience is portrayed as a dream (the convulsions being muted by succinylcholine), and she is seen waking up (undoubtably with a huge headache) from a soft bed with a pillow.

This movie could be considered a modern-day morality play for the mental health system. As Helen spouts platitudes about mental health, and is presumably continuing her medication, she slowly returns to her normal activities prior to the depressive episode, and the dimmer switch in her home is turned up.

Mathilda, by contrast, deteriorates conspicuously. She is non-compliant (whether or not her medication(s) actually work and what sort of side effects they have is not made clear to the viewers), drinks alcohol (if you are in fact taking SSRIs, you are officially advised to steer clear of both alcohol and pot), and has sexual encounters in alleys with different men. It is not made clear whether she is engaging in the unconventional sexual activity from her own free will, or if the men involved are threatening or blackmailing her, or if she’s paying her living expenses with prostitution.

After Helen leaves the house for the ECT (it takes at least a day to recover from the anaesthesia given in modern ECT, and she apparently has a couple of ECT sessions in a row, so the timeframe amounts to at least a couple of days) she returns to find the home environment showing evidence of neglect, disorganization, and “impulse control issues”.

The cast interviews included on the DVD were revealing.

Ashley Judd said that the scene where Helen is eating dinner with her family while undergoing major depression reminded another movie crew member of what it was like for her family when her mother had major depression.

Alexa, who played Helen’s teenage daughter Julie explained that the character she played went to live with her biological father for the sake of self-preservation even though she knew her mother “would be devastated by it”. Alexa added that she wasn’t sure if she’d be strong enough to do what her character did if she were in a similar situation with her family.

“The people around the person that’s depressed are often affected as well, and this film does a good job of showing that”.