Marwencol is the fictional miniature town creation of artist Mark Hogancamp, who uses the model-building and elaborate staged scenarios of his World War II-inspired tableaux as both occupational therapy and art therapy following an assault by a group of men which left him with physical injuries, brain damage, and a side order of PTSD. (It is explained in one of the deleted scenes from the “extras” section of the DVD that the fictional WWII era Belgian town’s name is an amalgam of “Mark” and some female friends’ names.)

Marwencol is the fictional miniature town creation of artist Mark Hogancamp, who uses the model-building and elaborate staged scenarios of his World War II-inspired tableaux as both occupational therapy and art therapy following an assault by a group of men which left him with physical injuries, brain damage, and a side order of PTSD. (It is explained in one of the deleted scenes from the “extras” section of the DVD that the fictional WWII era Belgian town’s name is an amalgam of “Mark” and some female friends’ names.)

Mark had had artistic inclinations before the assault, in which a group of teenage boys literally kicked his head and stomped on his face, after they had overheard him telling someone in a bar that he was an occasional cross-dresser. In the movie, he shows some of the drawings he had made prior to the attack, and explains that his hands are now too shaky to do similar drawings, so the model-making that goes into his modified dolls, miniature interior and exterior settings, and vehicles contributes to his own efforts to restore his coordination and former spatial abilities. Mark’s pre-injury drawings were used as State’s evidence in proving the extent of the damage to his brain by showing how the assault had affected his abilities afterwards.

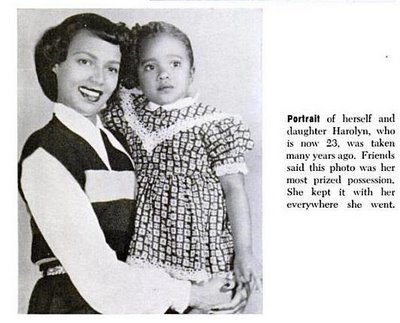

Mark’s extensive brain injuries had the effect of separating him from certain aspects of his past. His case of amnesia is serious enough that he claims not to clearly remember having been married. He had the wedding picture and every so often, he said, he would get (mental) “snapshots”, the occasional visual memory from his past, but nothing cogent, no clear narrative of the time they were together or particulars about her. He refers to the time after the injury as his “second life”. He not only got a second chance at life when he could have died, but he had the opportunity to “start fresh” in areas of his life he otherwise might not have. He showed on camera a set of self-written and illustrated graphic novel type books which he called “the alcohol journals” in which, prior to the injury, he had documented alcohol-motivated behavior. His former employer said on camera that he had often been absent from work due to his former life as a problem drinker. Since the amnesia from the injury resulted in his not being able to remember the feelings he got from alcohol, he said he decided to stay away from alcohol for the future, thus effectively ending a path of alcohol abuse.

It is explained elsewhere in the film that Mark received only a limited amount of occupational therapy following the reconstructive surgery on his face. The extent of the damage to his brain was such that Mark had to start life after the injury from almost the beginning, having to literally learn to walk again. Samples of writing exercises are shown in which Mark was directed to practice pre-writing motions in order to re-learn the strokes to write in cursive. The powers-that-be discontinued all such rehabilitative therapy well before it could be said that Mark was restored to his former abilities. As an example of this, in one part of the film, Mark is shown walking by the side of the road with a model vehicle on a string. He explains that though a disability such as his brain injury is not obvious to others, it affects common everyday activities such as this. He cannot “walk and look around” as others do. If he takes his eyes away from the white line at the side of the road on which he is walking, he soon finds himself straying far from the line and in danger from the traffic.

Less tangible, but still in need of remediation, is the emotional fallout from the event. Mark uses the sort of doll play (stories and scenarios in a tangible, time-specific setting) commonly associated with little girls, to work out some of his feelings about the assault and his place in the world in general. Having unwittingly re-invented play therapy, Mark voices the regret that he has no one to talk to. If he had psychotherapy or counseling of any kind, it has not been continued. He presumably lives on Social Security Disability payments and works 1 day a week in a restaurant called The Anchorage, where he had worked full-time prior to the incident. Most of the women he meets are married or otherwise uninterested, so he reproduces them in doll form and adds them to his storyline. His friends are baffled but honored to be added to his “collection” and fantasy world as “good guys”. The “bad guys” are society’s easy targets: male dolls in SS uniforms, though Marwencol is an otherwise strangely peaceable town where 1/6 scale German and Allied uniformed action figures lay aside their arms, go to the miniature bar, party, and have a good time. His fantasy world has a disproportionately high female population: 27 Barbies. After having been assaulted, he clearly identifies with the female characters’ vulnerability, and stages a scenario in which the Barbies gruesomely defeat the Nazis.

Mark Hogancamp poses and photographs action figures in the fictional WWII era Belgian town Marwencol.

A photographer friend gives him a camera, enabling Mark to photograph his tableaux. The photographs and story scenario become good enough for Eospus magazine to publish. The editor arranges an art exhibition in NYC at White Columns gallery for Mark’s photos and some of his dioramas. It is with mixed feelings and some trepidation that Mark puts together the pieces for the gallery show (he is afraid of having them lost, damaged, or otherwise taken away from him). However, though the PTSD causes him to fear large numbers of people and retreat from noise and hustle and bustle, he recognizes that people want to meet the artist, so being physically present in NYC for the gallery opening of his show is a necessary evil.