“Hale” is a new short documentary film about Hale Zukas, who helped make Berkeley the birthplace of the disability rights movement. He was diagnosed with cerebral palsy as a child. He went on to study Russian and math at UC Berkeley in the 1970s and he helped found Berkeley’s groundbreaking Center for Independent Living, which has become a nationwide model.

On the Way to School (Sur le chemin de l’école)

The French documentary “On the Way to School” profiles four children making their way to school in the developing world. One, 13 year old Samuel from India, is pushed and pulled 2.4 miles to school and home again by his two younger brothers in a makeshift wheelchair. The wheelchair consists of little more than a plastic lawn chair attached to a couple of bicycle wheels, but the ubiquity of the parts that compromise it mean the trio can get it fixed at a local repair place when the tire inevitably gets a flat… and the benefits of having a cheap plastic seat without upholstery become apparent when Samuel’s brothers decide to try pushing him through a couple of streams.

Samuel’s school does have a concrete ramp in front, and he’s met at the entrance to his classroom by a team of larger boys who carry him the rest of the way in. In an interview, Samuel tells of how fortunate he is go to school, when many of his peers don’t get the opportunity. He wants to become a doctor to help kids like him walk someday.

The supporting web site for the film explains that Samuel was premature when he was born, so his disabilities are likely due to cerebral palsy. They further reveal that Samuel is the only one in his family who can read, and that the arduous journey to school we see was due to the local village school being unable or unwilling to accommodate Samuel.

The Way(s) to School Foundation has been collecting donations to ensure that all four kids profiled can continue their schooling with scholarships, and have already bought Samuel a new wheelchair. Considering the rough terrain he has to cross every day, we at Disability Movies hope it’s a very rugged one suited for his environment.

Life Feels Good

Neither tearfully sentimental nor coldly scientific, “Life Feels Good,” Maciej Pieprzyca’s film about a man with cerebral palsy struggling to communicate to those around him that he is an intelligent, sentient human being, instead proves oddly entertaining. The protagonist, diagnosed as mentally retarded since childhood, delivers interior monologues that supply ironically normal counterpoint to the contorted sounds and spastic movements he makes. Brilliantly thesped by non-disabled actors playing the character as both child and grown-up, the film captures as much wonderment as frustration, and is filled with fully fleshed-out characters that defy simple categorization. Having swept the jury, audience and ecumenical prizes at the Montreal fest, this Polish feature could generate genuine arthouse interest.

Read more at Variety:

http://variety.com/2013/film/reviews/life-feels-good-review-montreal-1200596479/

Short Australian film The Gift is a big hit worldwide

From The Herald-Sun (Australia): http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/short-australian-film-the-gift-is-a-big-hit-worldwide/story-fnilxh2p-1226671089673

Short Australian film The Gift is a big hit worldwide

Staff Writer

The Daily Telegraph

June 28, 2013 12:00AM

THE Gift is the little Aussie film that could.

The little-known independent local movie starring Hugo Weaving’s son, Harry Greenwood, is one of the hottest tickets on the international short-film circuit.

And it was made on a budget of less than $10,000, pretty much what we’d expect the cast and crew of Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby to spend on lunch.

Created by brother and sister team Lloyd and Spencer Harvey, who have already won several awards for previous works, The Gift also stars Anne Tenney (The Castle and Always Greener), Mark Lee (Gallipoli), Hannah Marshall and Ben Mingay.

It tells the story of an 18-year-old boy, played by Greenwood, who is confined to a wheelchair with cerebral palsy and wants to lose his virginity on his 18th birthday.

“The Gift was extremely well received at the recent Palm Springs Short Film Festival,” Lloyd Harvey says.

Other respected international film festivals have heard the word, including two in LA which have added The Gift to their schedules.

The Melbourne International Film Festival early next month will also screen the celebrated short.

None of this means that the brother and sister team are suddenly flush with funds. However, according to Lloyd, critical acclaim on the short-film festival circuit means that, when the couple attempt to get a feature film produced, they’ll be taken seriously.

The Gift is certainly about an extremely sensitive area and Greenwood worked closely with the sex workers’ association The Scarlet Alliance and the Cerebral Palsy Alliance to ensure it sent the right message.

Sympathy for Delicious

In Sympathy For Delicious, we have a story which parallels the Satanic Verses in a modern, American, Christian context.

In Sympathy For Delicious, we have a story which parallels the Satanic Verses in a modern, American, Christian context.

“Delicious”, a.k.a. “Delicious D” is a youngish paraplegic man of no steady employment and no fixed address living on the streets and sleeping in his car while affecting a scruffy rocker-grunge look that isn’t entirely genuine grunge.

He eats at a small soup kitchen a priest runs out of a food cart on Skid Row. Though he tells the priest he wants to get into an SRO (good luck on that, the few that still exist are probably not wheelchair-accessible), the priest, who offers social services on a similarly small scale, tries to sell him on an assisted living facility and provides paperwork for it, but Delicious’ youth and pride cause him to reject that option and continue sleeping in his car while seeking out the occasional DJ-ing gig. He has some talent and fame at that, but the band he is seen auditioning for initially blows him off, for reasons of ableism.

Eventually his talent speaks for itself, and they grudgingly come around and accept him. However, another situation has come up which affects both his standing with the band and his situation on Skid Row.

He suddenly and inexplicably develops the ability to heal people of physical ailments in the miraculous fashion of Jesus in the Scriptures by laying on his hands and engaging in what appears to be a transfer of energy from him to them. It doesn’t work in all cases, and it doesn’t work on himself. (If the transfer of quasi-electric energy theory is correct, that explains why he cannot heal himself; which is one of the first things he tries soon after the healing power is made manifest through him; his energy would simply be feeding into a closed loop.) Yet crowds of people flock to him, and the priest encourages this in spite of Delicious’ intermittant abilities, because he hopes for a large donation from a man with a daughter who has Cerebral Palsy he hopes Delicious will heal. Though the priest pays for Delicious to stay in a hotel room, he is cagey about how much, exactly, he is collecting in donations from Delicious as a healing sensation. Delicious is suspicious about how much the priest is profiting (with the money ostensibly going towards building a proper shelter and social services agency) from his newly-developed paranormal abilities.

He feels used, and given a choice by our modern, secular society, he throws in his lot with the rock band, who also end up exploiting his healing powers for their profit; he agreed to participate in “Healapalooza” using his powers publicly at concerts much the same way he had drawn crowds on Skid Row, he merely hopes to see more of the money from the latter venture.

However, it ends in disaster when his healing power fails to work on a girl who is suffering the effects of an overdose, and he and his bandmates end up in court being charged with negligent homicide. The priest, this time inexplicably dressed in a business suit, testifies as a character witness.

The Nerves of Us

Nico, a man with spastic diplegia, contemplates the years of unnecessary damage to his bones and joints.

Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy (SDR) is the only surgery currently in existence that pretty much cures the average case of our spastic diplegia, a form of cerebral palsy that affects approximately 70% of the CP individuals known to science.

While orthopedic deformities may remain depending on how late the rhizotomy was performed, high tone is permanently dissipated, freeing the person to live life with normal muscle tone.

But most doctors won’t tell an adult with CP spasticity that. Most are still under the impression, for whatever reason, that SDR will not work or will not be healthy for a young or middle-aged adult with anything greater than the mildest degree of tone. But there have been several cases, including one as recently as September 2008 performed on a 28-year-old with moderate spastic diplegia, that shows that assumption to be baseless.

The main obstacle is simple: the medical establishment’s mode of thought is still dominant and holds all the power. And usually, we people with spastic diplegia and similar CP-spasticity, accustomed as we are to doctors having more answers and experience than we do, do not look in to the things we are not given.

Read more at rhizotomyfilm.com.

Sexual healing: A new documentary tells the story of a remarkable woman

Mark Manitta loves sex. Can’t get enough of it. But being confined to a wheelchair with cerebral palsy has cramped his style. So, for the past seven years, he has been a client of Sydney sex worker Rachel Wotton.

“People do not understand the difference that sex makes,” Manitta explains in the new SBS documentary Scarlet Road, speaking through a voice machine that makes him sound like a randy Stephen Hawking. “Part of having cerebral palsy is spasticity and muscle spasms. I need sex all the time to make my muscles relax. And I like sex.”

Three years in the making, Catherine Scott’s documentary explores the relationship between people such as Manitta and Wotton, who specialises in disabled clients. The film, which has been nominated for a Walkley Award, provides a rare glimpse into a world that most people are oblivious to or would rather pretend doesn’t exist.

“People assume disabled people don’t have the same biological needs and desires that everyone else has,” Wotton says. “But sexual expression is a basic need for everyone, not just for those who can walk and talk freely.”

Outspoken, articulate and utterly unflappable, Wotton, who has spent 17 years in the industry, describes herself as a “whore”, a brazenly self-deprecatory term that belies her intelligence and ambition. But it’s her empathy and pragmatism that resonate most strongly.

“Part of my reason for doing the film was to wipe away the ‘us and them’ mentality,” she says. “We’re all one car accident away from being in the same position as these guys. Tomorrow we could all wake up out of coma and not be able to eat let alone have sex or touch ourselves. What I say to people is imagine the next time you go to have sex or masturbate having to call your mum and have her organise it all for you.”

Indeed, for parents brave enough to recognise their disabled children as sexually mature adults, sex workers such as Wotton are a godsend. “I remember the first brothel we visited,” Mark’s mother, Elaine, says. “It was supposed to be wheelchair accessible but it wasn’t. So I had to carry Mark up the stairs. Then I just broke down and cried the whole time I was there. But then as the years have passed I have got to enjoy waiting around and meeting the girls. It’s just become part of life.”

Getting the clients and their parents to come on board wasn’t as hard as you might think, according to Scott. “People with disabilities want to be viewed as whole beings.

“Think about how important your sexuality is to how you are perceived. These people aren’t seen like that, so you can imagine how that makes them feel.”

One of Scott’s favourite scenes is when wheelchair-bound multiple sclerosis sufferer John Blades, who sadly passed away only days before the documentary went to air, is sitting at an outdoor cafe with friends, having spent the previous night with Wotton. “It was just a great night of sex,” Blades tells them. “It made me feel like a real bloke again.”

Scott hadn’t planned to take three years to make the film. “But it actually worked out really well,” she says. “Because it took so long, all these things happened, like Rachel fell in love.

“In the end, you get a picture of her as a real, rounded person who is doing this extraordinary work.”

Read more: http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/tv-and-radio/sexual-healing-20111125-1nxkc.html

“How Does It Feel” profiles man with CP who becomes singer

Sometimes dreams really do come true.

For Kazumi Tsuruoka, it began with a passion for music and a life-long desire to sing, even though he had always been told he couldn’t.

Singing is a daunting enough task on its own, but Tsuruoka had an added complication — cerebral palsy — which impaired his motor control and speech.

Still, he didn’t give up. He sang on his own and at 58 years old, began taking singing lessons. The result had a far reaching impact on both the singer and those who listened to him.

“As soon as I saw it (Tsuruoka’s one-man show) it just blew me away,” said Lawrence Jackman, who made a documentary film on the singer’s journey from learning to sing to creating his own show. “It was an incredible performance.”

The film, How Does It Feel, will be shown at the Barrie Film Festival’s Director’s Brunch next weekend. Jackman and Tsuruoka will both be in Barrie for the screening, the brunch and a question-and-answer session.

The film, which is about 40 minutes in length, takes the form of interviews interspersed with a few songs from Kazumi’s one man show and scenes of his work with voice teacher Fides Krucker.

“It kind of recreates the process they went through from when they first started working together to the realization he actually was a talented singer (and) that she could work with him through to putting a show together,” said Jackman, adding that Tsuruoka was a natural performer.

The show was called CP Salon and it was staged for the first time in Vancouver, did a run of western Canada and the Yukon two years ago and played at several college campuses in Toronto.

Four songs from Tsuruoka’s one-man show are included in the film — rhythm and blues tunes such as Smokey Robinson’s Tracks of My Tears.

In the context of the show and the film, the songs take on a different meaning when he’s singing them.

Jackman is a Toronto-based director and editor who has worked on many award-winning documentary films. In 2005, he was nominated for a Gemini award for editing the documentary Animals.

Most of his work is for independent films. He also has a long association with the National Film Board of Canada, which produced How Does It Feel. This film also marks Jackman’s first time directing for the NFB. While most of his focus is on directing these days, he continues to enjoy the editing process.

“That’s when the story comes together,” he said. “Anything can happen during the shooting process and then, when you get to the editing stage, you’ve got all the elements so there’s no going back at that point.

“That’s where you find the story you actually collected. You have to kind of throw out your expectations and just see what’s there to be filmed. It’s a very exciting process.”

Jackman fell into films when he was looking for work and his first job was in the editorial department of a television show. It was enough of an introduction to appeal to him. The rest he learned from the ground up.

His interest in documentaries has never wavered.

“One of the reason I’ve always focused on documentaries is that there’s always going to be a interest for me — no matter what the subject, who’s making it, what the budget is,” he said.

“Because you’re dealing with real people and real issues, there will always be something that is captivating.”

One of his interests is music and How Does It Feel is his second film — the first was about a young saxophone player. With How Does It Feel, Jackman wanted to explore how music affects us both emotionally and physically.

After the film has completed the circuit of small film festivals, it will likely be shown on television before winding upon the NFB website. There is also the hope that How Does It Feel will have a strong educational run, both being shown at and used by schools.

The Director’s Brunch takes place on Sunday, Oct. 23 at the Mady Centre for the Performing Arts, Dunlop and Bayfield streets, beginning at 11 a.m.

Tickets are $25. The BFF has a box office at Bayfield Mall Oct. 16-20 and at the Imperial Theatre Oct. 15 and Oct. 20-23.

For more information, visit www.barriefilmfestival.ca.

C4 lines up Paralympic doc series in UK

From Realscreen:

UK terrestrial Channel 4 has commissioned a 10-part documentary series following the lives of a range of different Paralympians, ahead of the 2012 Olympic Games which are being held in London next year.

Best of British will focus on Paralympic athletes from a range of different sports, including racing, sitting volleyball, swimming, shot putting, wheelchair rugby, Cerebral Palsy football, para equestrian, tennis and blind football.

The series promises to reveal “the brutal training regimes and the fierce rivalries as they compete for a place in Paralympics GB.”

The series will premiere later this year, and is produced by Two Four. It was commissioned by C4?s commissioning editor for documentaries Mark Raphael.

Read more: http://realscreen.com/2011/08/30/c4-lines-up-paralympic-doc-series/#ixzz1WsoYr3Ht

Able actors in disabled roles ‘like blacking up’

From Independent.ie:

Casting able-bodied actors in disabled roles is as repulsive as having white actors “black up” to play black roles, an Irish actor in the latest summer blockbuster has said.

Storme Toolis (18), whose father is investigative journalist Kevin Toolis from Achill in Co Mayo, was delighted to land a role in the feature film adaptation of the Channel 4 sitcom ‘The Inbetweeners’.

Ms Toolis, who lives in London, has cerebral palsy and is a wheelchair user.

She landed her big break when she turned up at an open audition to cast extras in the film about four loveable but idiotic 18-year-old boys.

But Ms Toolis was called back a couple of weeks later and offered a more substantial role.

Within weeks she was on the set in Majorca, having wet towels thrown over her by cast member Blake Harrison, who plays Neil and is famed for his dance moves.

“I really enjoyed the experience. It just takes a bit more effort to employ someone with a disability. You need wheelchair accessible transport etc, but it is a better and more honest approach to the role and always comes off with more authenticity,” she said.

The ambitious teenager, who calls Mayo her “second home” said the acting world was extremely challenging for a person with a disability.

“It is just so hard to land a part and it is not because there are no disabled characters. It’s just non-disabled actors who seem to get them,” she said. “The majority of the ‘disabled’ characters on TV, such as the boy in the wheelchair on ‘Glee’ are in fact able-bodied actors.

“Years ago white people used to ‘black up’ to play black characters but that would not wash these days. There would be a huge backlash, yet there seems to be different rules when it comes to disabled people,” she added.

– Edel O’Connell

The Fighter

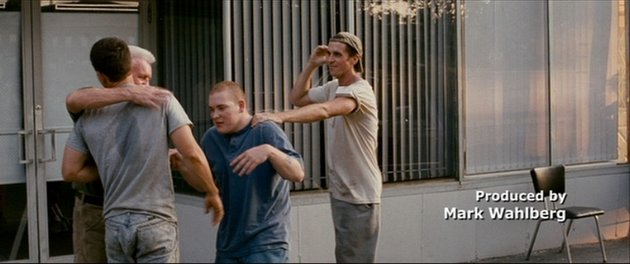

The opening credits of The Fighter depicts brothers Dicky Eklund and Micky “Irish” Ward running down the streets of Lowell Massachusetts, greeting their friends with bonhomie, including a man with cerebral palsy who they hug and kiss and say “I love you, Ray. I love you.” (Though it would be considered culturally inappropriate to greet an able-bodied man in the same fashion, Ray doesn’t mind as he is Micky’s godson and favorite sparring partner in real life.)

The opening credits of The Fighter depicts brothers Dicky Eklund and Micky “Irish” Ward running down the streets of Lowell Massachusetts, greeting their friends with bonhomie, including a man with cerebral palsy who they hug and kiss and say “I love you, Ray. I love you.” (Though it would be considered culturally inappropriate to greet an able-bodied man in the same fashion, Ray doesn’t mind as he is Micky’s godson and favorite sparring partner in real life.)

Dicky and Micky are boxers and home-town heroes, though Dicky has been slowly falling from grace due to his addiction to crack. An HBO documentary that everyone thought would chronicle Dicky’s comeback instead turns out to be his downfall, and Micky must advance his boxing career without him.

Micky is not without some physical challenges of his own; repeated injuries to his hand (shown in the movie as the result of police brutality) necessitate a regimen of physical therapy and training. The movie does not depict the surgery Micky Ward underwent to correct the problems with his hand, where, at his own expense, bone was taken from his pelvis and used to strengthen and fuse the bones of his hand.

Ray and his aging father are seen ringside a couple of times later in the movie, and Ray seems to be moving and speaking more easily. The film doesn’t go into it, but as People magazine article Micky Ward: Fighting Spirit explains, perhaps that’s because the real-life Micky started foundation Team Micky Ward Charities to help disabled youngsters gain confidence through physical training and conditioning.

Based on the book Irish Thunder: The Hard Life & Times of Micky Ward.

Wheel Chair

“Wheel Chair” is a 1995 Bollywood movie, minus much of the singing and dancing, available on Netflix in the Bengali language with English subtitles. Susmita, a typist, is working late one night when three men attack her in the stairwell with the intent to rape her, causing her to fall and break her neck. Someone calls an ambulance, and the doctors at the hospital she’s taken to decline to do surgery (presumably to stabilize her neck) for fear of affecting the “Vegas” nerve. (Surely they mean vagus. One would hope that a doctor has a good grasp of geography; after all, they’d better know how to locate the islets of Langerhaans.)

Susmita’s head is put into a primitive Hannibal Lechter-type headgear that doesn’t look terribly stable, ostensibly to provide traction. The company Susmita worked for takes responsibility for paying for her care and rehabilitation, and she is brought into the care of Dr. Mitra, who runs a home for “neurological disabilities” and is also a paraplegic himself.

Dr. Mitra acquired his disability in a car accident in England on his way to a neurology conference, and “somehow found his way” back to India. (It is fortunate that he became a neurologist before becoming disabled, as people with disabilities who want to enter the medical profession often face obstacles and prejudice from medical schools.) The small clinic/home he founded in Calcutta has lost its funding from the government, and the board of directors wants to sell the land to put up a nursing home. Dr. Mitra must balance his time between treating patients, fighting with his own board of directors, and cajoling money from businessmen to keep the home running and the patients fed. He is portrayed as being a professional inspiration to his patients, yet privately he drinks, relies on the assistance of the able-bodied staff for tasks a paraplegic can usually do by themselves, and occasionally wishes out loud for death just as his patients constantly do.

Susmita is wheeled in on a gurney through the men’s ward, where she is frightened by the ogling of the male residents. They are introduced as Nantu, a young man who has been disabled from birth (probably from cerebral palsy, although he’s being treated with Vitamin B):

Mr. Shatadal, a belligerent older man on crutches who fantasizes about dying and being taken away by a white camel with a golden saddle blanket:

and Amin, a tall, withdrawn, intimidating man who was an astrophysicist before he had a nervous breakdown.

The handsome physical therapist Santu sets to work on the depressed Susmita, who agrees to work at therapy only to regain use of her hands and arms to kill herself. He stretches her limbs and painfully puts her face-down in a hammock when a bedsore begins. One night, against the orders of Dr. Mitra, Santu engages in what he calls “shock therapy”; he slides his hand up Susmita’s thigh under her clothing in order to deliberately remind her of the rape. In a panic, she moves a toe. This is hailed as a breakthrough instead of a violation of professional boundaries, and it fulfills the Disability Movie Cliche and ludicrous ableist conceit that disabled people can be cured by attention from the opposite sex.

The most realistic aspect of the movie Wheel Chair is the agonizingly slow pace of recovery for each resident. By the time Susmita is ready to return home two years after arrival, Nantu has progressed from learning his letters to slow reading (though everyone discourages him from hope of ever having a wife). Amin has displayed anger over conditions in the home, pushing Dr. Mitra over and then returning him to his wheelchair, and later writing an inscrutable equation on a slate. Mr. Shatadal reveals himself to be a self-made man from selling nuts and bolts to the American army at a huge markup, writes a large check to the home, and then suddenly goes blind and dies within minutes.

After Susmita returns to her mother’s home to begin a prescribed regimen of physical therapy and slow hunt-and-peck typing, Santu asks Dr. Mitra of the advisability of marrying her. Dr. Mitra assures him that she will be able to bear children, so Santu declares to Sumitra’s mother that he wants to “take on full responsibility” for her. Susmita is in tears at this… charming proposal, but though she ascribes to the common belief one must be able-bodied to be married she eventually acquiesces, saying that she’ll put down the returning strength of her upper body as capital and work for the rest. Santu and Susmita settle down into a house on a river, where Santu is last seen happily carrying Susmita to a wheelchair on a patio.