[easyazon-image align=”left” asin=”B00003CWHQ” locale=”us” height=”160″ src=”http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51N5J1Q2DBL._SL160_.jpg” width=”111″]Supposedly Werner Herzog’s [easyazon-link asin=”B00003CWHQ” locale=”us”]Even Dwarfs Started Small[/easyazon-link] is an allegory on the problematic nature of fully liberating the human spirit, but we at Disability Movies think that might too sophisticated an interpretation for a film that should have been titled “Dwarfs Gone Wild”. It’s 96 minutes of vignettes of the worst stereotypes of little people behaving badly at an isolated mental asylum, strung together with little semblance of a plot. They cackle maniacally for no apparent reason, break dishes and ruin perfectly good food, look at naked average-height women in an art book yet can’t figure out how to have sex themselves (what?), torment blind dwarves, make a car drive around in circles, set houseplants afire, and, at the crux, crucify a monkey. Sure, you could read all that as a commentary on the wastefulness and depravity of modern society, but why would you need little people for that?

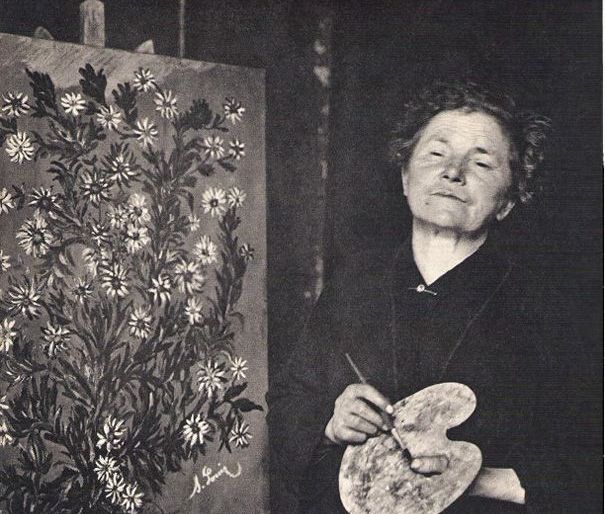

Séraphine

[easyazon-image align=”left” asin=”B0031REQKE” locale=”us” height=”160″ src=”http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/515Iid3xpPL._SL160_.jpg” width=”113″]A portrait of the artist Séraphine de Senlis (born Séraphine Louis), [easyazon-link asin=”B0031REQKE” locale=”us”]Séraphine[/easyazon-link] explores the relationship between her and influential art collector Wilhelm Uhde after their initial meeting in 1912. Aging Séraphine was then working as a maid, subsisting on whatever crumbs her employers left for her and spending any available centime on base white for her paintings. Uhde happens to see some of her early work and buys everything available, enchanted by what he calls her Naive style. (Her employer and community is skeptical, finding her art almost terrifying; it displays the horror vacui characteristic of the art of schizophrenics.) They also manage to find some common ground despite the differences in their ages and socioeconomic classes; Séraphine is perceptive enough to recognize the signs of depression in Uhde, and advises him to spend some time in the woods touching the plants. But her first benefactor must soon leave the country in a hurry, telling Séraphine she must continue to work on her art.

Séraphine already considered this her mandate from heaven, and becomes more and more destitute as the war goes on and the jobs available to her began to dwindle. Certain people are charitable to her over the years, and Uhde finally returns to set her up with an exhibition–“Painters of the Sacred Heart”–and for a time, a regular salary. Séraphine is ill-prepared to handle success and quickly starts living beyond her means, sending Uhde bills for a house and costly wedding dress (though she doesn’t seem to have a groom lined up).

With the Great Depression in full swing, Uhde breaks the news that he’s unable to get her a gallery show or continue buying her paintings. Before she is forced to sell off all her new possessions, though, Séraphine experiences what might be considered a cross between a religious experience, a piece of performance art, and a psychotic break. Clearly taking a page from Lives of the Saints, Séraphine trudges through the streets at dawn dressed in the bridal gown, knocking on each door and leaving silver candlesticks and utensils before the occupants answer. A crowd of women gathers to witness silently, and someone fetches the police. They gently escort her to a waiting van and drive her to a mental asylum typical of the period; inmates in rags and at each other’s throats. Her artistry found no outlet there, and she was cut off from the natural surroundings that helped with her depression.

The film depicts Uhde visiting to observe her from afar and paying for better accommodations (so that she can walk outside and sit under a tree in the final moments of the film), but there’s no evidence he did that in real life. Although Uhde reported that she had died in 1934, some say that Séraphine actually lived until 1942 in a hospital annex at Villers-sous-Erquery, where she died friendless and alone. She was buried in a common grave. Uhde continued to exhibit her work, and today Séraphine Louis’s paintings are exhibited in the Musée Maillol in Paris, the Musée d’art de Senlis, the Musée d’art naïf in Nice, and the Musée d’Art moderne Lille Métropole in Villeneuve-d’Ascq.

Jane Eyre

This most recent motion-picture version of Jane Eyre is a somewhat different cinematic re-telling of the novel with a greater emphasis on the idea that it is a gothic novel, and that therefore the set and settings must be dark and dreary as is the greater part of the plot. Many of the indoor scenes take place at night, and are lit by only a candle or a lamp, and there are a number of outdoor scenes which take place at dusk or in overcast weather. Though I can’t say I am entirely comfortable with the sheer amount of darkness thus utilized in the film, I have to take my hat off to the lighting director and staff for actually carrying this off without the obvious blue-filtered fake “night” so often seen on screen.

This most recent motion-picture version of Jane Eyre is a somewhat different cinematic re-telling of the novel with a greater emphasis on the idea that it is a gothic novel, and that therefore the set and settings must be dark and dreary as is the greater part of the plot. Many of the indoor scenes take place at night, and are lit by only a candle or a lamp, and there are a number of outdoor scenes which take place at dusk or in overcast weather. Though I can’t say I am entirely comfortable with the sheer amount of darkness thus utilized in the film, I have to take my hat off to the lighting director and staff for actually carrying this off without the obvious blue-filtered fake “night” so often seen on screen.

Unlike many other cinematic adaptations of Jane Eyre, which center on her adult career as a governess/village schoolmarm, and the restraint she practices when the legal and social impediments first to her relationship and then to her marriage are made clear, this one goes into greater detail about Jane’s unhappy experiences in childhood, with Amelia Clarkson, a young girl actress, playing Jane at a young age at the beginning of the movie. Jane Eyre lost her parents in her preteen years, and is adopted by an aunt who had promised her father on his death bed that she’d take Jane in. But Jane’s spirit and willingness to stand up for herself don’t sit well with the aunt, who favors her own older boy. Things come to a head when the boy tries to steal a book from Jane that had belonged to her uncle and they tangle in a physical fight, in which the boy ends up hitting her head so badly that blood comes out of her ear. (Yes, Jane may have ended up with head injuries and/or inner ear injuries as a result of these fisticuffs, and she only ends up the worse for it when the aunt and servants break up the fight). Jane ends up being the one punished for the perceived transgression by being locked in the “red room” (a parlor with red damask wallpaper) concerning which she expresses a belief that it is haunted. It is after this incident that the aunt decides to solve her familial problems and “cast-off’ Jane, sending her to the strict boarding school where dull gray dresses, a Calvinistic guiding philosophy, and corporal punishment are the order of the day.

In one incident at the school, Jane is caught looking elsewhere while the teacher is talking. She is made to stand on a high-legged chair while being caned, and the headmaster, upon witnessing the incident, declares an additional punishment for Jane: she is to stand all day upon “the pedestal of infamy” and is to be denied food and water, as well as the friendship of others at least for the day. One girl, Helen, defies the ban and sneaks Jane some buttered bread after the headmaster and the class have gone and Jane is standing alone in the empty classroom. Helen later sits with Jane in the garden and tells her that there is “an invisible world” of spirits all around her, whose purpose is to protect her. (She knows this because she “can see them”. Helen is thus quite an advanced mystic for a little girl, or a schizophrenic, or perhaps a bit of both.) This being the Regency era, when people frequently died of infectuous diseases, Helen shortly thereafter becomes obviously sick, and worsens to the point of dying. The boobs running the school continue to allow Helen to remain in the common room inhabited by the rest of the girls, a circumstance which allows Jane to be with her on her deathbed. Helen declares she is happy to be going home to Heaven, and expresses an optimism the authority figures in Jane’s life don’t have about Jane joining her there at a later date.

Jane’s adult career begins with her being given a choice between being governess of a little girl who speaks only French living in a grand house where “the master” comes home only infrequently, or teaching “cottagers’ daughters” in a village school.

Though she initially shows a willingness to take the village schoolteacher position, she ends up taking the grand house governess gig (perhaps because finding one who speaks fluent French is so rare in the far-off English countryside?) and building a relationship of rough equality with Rochester which would lead to a proposal, followed by public displays of affection (in their world, that was “action”) and a double-time trip to the altar, which was interrupted by a concerned party who revealed the continued physical existance of Bertha Mason, Rochester’s previous wife. (Unlike in other cinematic portrayals of Jane Eyre, in this one, Jane finds out about the existnce of the other woman after having been successfully led to the marriage ceremony and has even more cause than in the other movies to tell Rochester, “sir, you are deceitful!” and to remove herself from his household, as the “proper” and “moral” thing to do according to the sensibilities of the times, even though she still has feelings for him.)

Rochester justifies his conduct and his withholding of information about the situation of his first wife from her by saying that mortal human laws are a mere guideline and have no bearing upon a situation so obviously unjust, the idea of marriage to a madwoman being effectively rendered null and void by very reason of her insanity, but unrecognized in that time and place as grounds for legal divorce, or, apparently, nullification on the part of the church.

He rationalizes having essentially imprisoned Bertha in a secret room in the house and concealed her existence as a humane alternative to having taken her to one of the existing institutions of the day for the mentally ill, which were often conspicuously inhumane, such as “Bedlam, where they bait the inmates and use them for sport”, and where tours were held for the amusement of the public (from which the tradition of “grand rounds” doubtlessly derived), the mentally ill not having the benefit of the privacy laws of our day.

(It was only in the late 19th century that Dorothea Dix conceived of professionally managed State-run institutions in the USA as a humane -for the 19th century- alternative to the mentally ill being sent to prison or being kept in such dubious circumstances in their family homes).

The fact of the Bertha’s continued existence and the hidden cell for her with a concealed door behind a tapestry cleared up a few suspected-to-be paranormal incidents earlier in the movie: the mystery of how a small fire got started in a room near the hidden chamber, and why Adele, the French girl, believed that there was a woman with long wild hair and “sapphire eyes” who walked the halls of the manor house at night, and was a vampiress.

Bertha is not shown as a fully-developed character in this movie: when the door to her cell is opened in Jane’s presence, Bertha shrinks away like a vampire exposed to garlic. Moaning and whimpering, she comes back to the threshhold to embrace her husband, her long, thick hair obscuring her features.

While the mental illness of Rochester’s wife is unspecified, Jane’s aunt may well be a sociopath. While working for Rochester, Jane receives news that her distant uncle with whom she had lost contact as a child had died, and that the aunt who had sent her away had a stroke upon hearing the news. She goes to the aunt, who makes a quasi-deathbed confession. Finally feeling a touch of remorse for her deception, after having previously accused Jane of deception when she was a child, Jane’s aunt confesses that she “wronged her twice”, first by sending her to the boarding school when she had promised Jane’s father that she would take Jane in, and later on, in an incident which Jane had no knowledge of, while Jane’s uncle was still living, in an effort to do Jane out of her inheritance, she lied to him when he wrote asking for Jane’s contact information, misinforming him that Jane had died of typhus while at the boarding school.

Jane manages to convince her uncle’s executors of the truth, and they eventually track her down, and she is informed that she is to be a wealthy woman, which is good news primarily on the grounds that wealth buys independence.

In order to physically separate from Rochester, she takes the village school job. It is however, while she is working at the village school job, that she is proposed marriage by St. John on pragmatic rather than romantic grounds to join him as a Protestant missionary in India.

Though she had been itching to see the world (she looked wistfully at the globe when she taught her young charge geography and voiced regret at never having seen a city as well as frustration with the fact that women were not permitted to do a lot of things and “have adventures” in her time) she turns him down because she is still carrying the torch for Rochester.

In an ambiguously happy ending, she reunites with Rochester, but only after his legal wife escapes the secret room, successfully burns down the house and commits suicide by jumping off the roof. As Rochester had been blinded in the fire, he recogizes Jane by gently feeling her hands and face.