Guzaarish (Hindi for “Request”) is the Bollywood remake of “Whose Life is it Anyway?”, and yet another example of the “right to die” disability movie trope.

Guzaarish (Hindi for “Request”) is the Bollywood remake of “Whose Life is it Anyway?”, and yet another example of the “right to die” disability movie trope.

The story centers around Ethan Mascarenhas, once a famous magician, who became a quadriplegic when his best friend betrayed him during a dangerous trick. Ethan has seemingly done well as a quad; he wrote a popular book and appears to have toured to promote it, he’s a Radio Jockey of a popular program called Radio Zindagi, has a romantic if gloomy mansion on a hill, two live-in servants and a nurse, and a sip-and-puff motorized wheelchair. From his home-based studio he exhorts his radio listeners to find beauty in their lives and boasts about his program being the most joyful on the air.

That’s why it’s so surprising when, on his 14th anniversary of becoming a quadriplegic, Ethan suddenly announces that he wants to end it all, and instructs his best friend (a lady lawyer) to file a petition with India’s courts for euthanasia. (Or, as he calls it on his radio program, “Ethanasia”.)

He also suddenly begins snapping at his caregivers and even makes a sexually harassing remark or two to Sophia, his nurse. Disabled viewers probably start wondering if Ethan has some underlying mental health issues at this point.

While it is impossible to deny that many people with disabilities–particularly the newly disabled–are indeed suicidal, “right to die” movies such as Guzaarish are problematic because movies are the primary vehicle for the able-bodied to learn about the lives of the disabled. Suicidal tendencies among the disabled are seen as a perfectly rational, and even noble, response to their condition; a movie such as this only reinforces such perceptions. Depression is thus left untreated and available services unapplied for. Studies show that once disabled people are offered adequate services, pain relief, and adaptive equipment to maximize their independence, they become much less likely to be suicidal.

And indeed Guzaarish bears this out; during the court hearing, it is revealed that Ethan’s mansion is mortgaged to the hilt, and he only has enough savings to cover Sophia’s salary for two more months. Further cracks in Ethan’s cheerful facade begin to appear upon examination. He may have a proper motorized wheelchair, but he only uses it in the beginning of the film. The rest of the time, he’s hauled about slumped in an ill-fitting manual wheelchair. Perhaps his town isn’t particularly wheelchair accessible, nor does he seem to have access to an adapted van or paratransit services. But that doesn’t explain why he hasn’t installed himself on the first floor of his mansion instead of the second, nor added ramps about the extensive grounds. Perhaps he wouldn’t be so depressed if he made an effort to get out more than once in a decade?

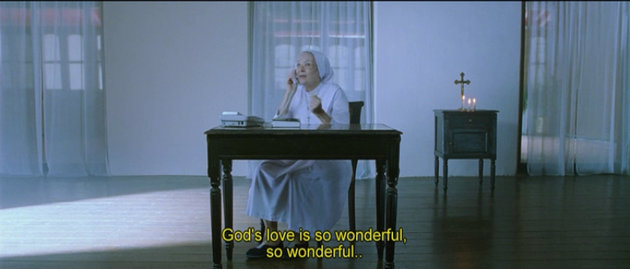

Any quadriplegic viewing the above image is now wondering why Ethan bothered to go through the court system, when the means of offing himself are already at his disposal. Clearly Ethan is crying for help, and those cries are amplified when he puts Ethanasia up for a vote on his radio program after the courts deny his initial petition. Most callers vote no; a handful, including Ethan’s former lover, crushingly vote yes. If Ethan wasn’t depressed before, he surely is now.

A judge decides to hear Ethan’s case, and even moves the courtroom to the foyer of Ethan’s home to accommodate his trouble getting around. Ethan uses showmanship to lock the prosecutor into a trunk, and when he begs for release before a minute is up, Ethan tries to make the point that the prosecutor couldn’t tolerate being confined for even a minute. The judge still denies his request, but Ethan has one more ace up his sleeve: Sophia.

Sophia and Ethan declare their love for each other, and she agrees to marry and then kill him, damn the consequences. They have the most uncomfortable wedding imaginable, with the groom dressed up on his deathbed insulting his guests one by one. Ethan’s doctor friend nearly leaves, but is convinced to stay. All pile on the bed to wish him farewell. If there’s one thing to be grateful for, it’s that Guzaarish narrowly avoids the disability movie cliche of the disabled character dying onscreen.