The Temple Grandin biopic: “Clinically Accurate” and only slightly fictionalized.

I was afraid I was not going to like this picture. I’d heard and read about Temple Grandin, an autist who has gained fame for being able to accomplish concrete measures of worldly success and for being verbal enough and sophisticated enough to describe what certain aspects of autism are like, and give advice on how to help other people with autism relate to the world.

But anyone in the public eye is bound to have significant parts of their story exaggerated and/or white-washed in public portrayals. I’d expected that this picture would be the sort of hagiography a PR firm or an autism-related non-profit organization might use to promote Temple’s speaking engagements.

However, I was pleasantly surprised by the veracity, or at least verisimilitude, of the cinematic portrayal. Though it is made clear that Temple has achieved a lot, and that her autism symptoms become less obvious to others as she gets older and develops more coping skills and gains intellectual knowledge of the behavior and expectations of others, it is clear that Temple has warts (metaphorically speaking) and doesn’t experience a magic cure.

Watching the version of the movie with commentary is instructive, as some of the commentary is given by Temple Grandin herself, who described the scenes where Claire Danes portrayed her panicking in sensory overload situations, self-“stimming”, and opening conversations with formulaic greetings in some parts of the movie as “clinically accurate”, to which I concur, having experienced similar sensory overload situations myself.

Temple did, however, have a veritable “perfect storm” of opportunities, chance meetings, and mentors whose influence allowed her career to take shape and grow, in addition to an exceptional mechanical aptitude that she exercised and demonstrated on her aunt’s ranch. It was because of her extended stay there that she developed an increasing interest in cattle and their behavior, even at one point bonding with the cattle by lying down in the cattle pen and letting the cows lick her. (That scene in the movie is not CGI, and Temple notes in the commentary that one can do this safely with cattle, so long as it is an enclosure containing only cows or steers, not bulls.)

Temple claims that her autism gives her an intuitive understanding of cattle and other prey animals; perhaps because she observed that often the same things in the environment that raised her anxiety levels would “spook” cattle as well. Observing the problems in the cattle-handling processes in the stockyard design common to that era allowed her to do what every successful entrepreneur claims: to “find a need and fill it”. In this case, it was the need for processing facilities which kept cattle calm and reduced accidental cattle deaths and stampedes, which was initially a “hard sell” for a cattle industry which was at that time male-dominated, rife with sexism, and resistant to change. (Which one had the autism again?) There was even a point in time when a rule had been laid down that women weren’t allowed in the cattle yard she was studying. I had to smile when she adopted the animal kingdom’s age-old strategy of camouflage: after buying a pickup truck and covering it in mud, she donned overalls, and rolled in the dirt. With her hair tucked underneath her cap and sunglasses covering her eyes, the yard boss waved her right in.

I liked the fact that the movie portrayed the way in which her spiral-shaped cattle processing line worked with the natural behavior of cattle and the way in which it was set up intuitively led the cattle to move through the facility without bunching together or stampedeing. I especially liked how they portrayed one of the cattle going through the dip vat in her facility without incident, and then using the little stairs she had built in to climb safely out of the dip, in contrast to the older-style processing line in which cattle could tip over and drown trying to get out of the dip vat and often had to be pulled out. Though the cattle yard personnel actually sabotaged her first facility, evidently something changed at some point: the end of the movie noted that in the present time, over half the cattle handing facilities in the US use the cattle processing system she designed. “Nature is cruel, but we don’t have to be” she said.

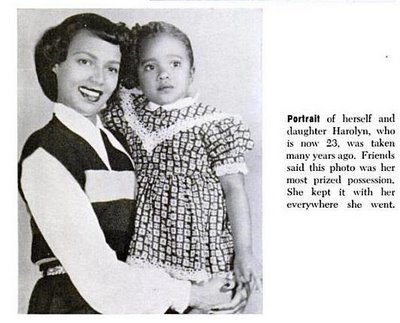

She was fortunate to have a number of mentors who helped her as her higher education and then later her career developed, from the high school science teacher who was able to recognize her visual thinking for what it was, consider her “different, not less”, and channel her aptitudes into animal husbandry, a marketable, if then non-traditional career for women; to those whose help took less direct forms, such as that of the secretary for a cattle journal who took her shopping for the decorative Western wear outfits which are now her trademark look; to the office worker who slammed a can of Arrid Extra Dry on the desk in front of her and flatly told her to use it.

The opening scene of the movie, with deafening sound from the engines of an old-fashioned prop plane and heatwaves shimmering off the tarmac as Grandin deplaned and met her Aunt Helen for an extended stay on her working ranch, did what I would have done in a cinematic story told from the point of view of someone with an Autistic Spectrum Disorder: presented a picture of a situation of “sensory overload” and gave the audience an opportunity to develop an intuitive understanding of the kind of situation that can be uncomfortable if not overwhelming for a person with autism and “set them off”.

Indeed, throughout the movie, Temple gets “set off” by loud noises, crowds, cafeteria lines, unfamiliar environments, and more. When she saw how a “squeeze machine” calmed cattle and made them hold still for vaccinations on her aunt’s ranch, she gave it a try and found that it has the same effect on her without triggering the sensory overload and panic a hug from another person did.

Temple notes that in real life, she used her first self-constructed squeeze machine in high school, though the movie portrays her as having constructed it as she was about to go to college. She did get into trouble with the college administration and alienated her first roommate when they thought she was using her device for some sort of psychologically unhealthy sexual self-stimulation. (In the movie, this was determined by a psychiatrist so Freudian he affected the appearance of his role model.) Temple got to keep the “hugging machine” after she designed her own psychological research experiment proving that it is effective for calming other (non-autistic) people. The squeeze machine, it is later noted, becomes a recognized means to calm autistic children and get them more accustomed to touch. Ironically, Temple revealed in her commentary that she takes antidepressants (and has for 30 years) in order to prevent her propensity to panic in sensory overload situations. Admittedly, modern SSRIs were not widely available during the time period in which much of this movie was set, but it is a bit disappointing to think that her non-drug calming method is by her own tacit admission gathering dust.

27×40 movie poster