Watch the trailer of the biopic of the late quadriplegic cartoonist John Callahan, who was paralyzed in a car accident at age 21 and turned to drawing as a form of therapy.

Cronicas Chilangas

[easyazon-image align=”left” asin=”B002WKTFXO” locale=”us” height=”75″ src=”http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51bgfc9ISFL._SL75_.jpg” width=”75″][easyazon-link asin=”B002WKTFXO” locale=”us”]Cronicas Chilangas[/easyazon-link] is one of those films following several characters whose lives intersect in some dramatic fashion, two with different disabilities. We’re introduced first to schizophrenic “El Jairo” who comes to believe the Men in Black are trying to recruit him; his fellow gangsters try to give him a wide berth, but since he’s related to the bossman he can’t easily be disarmed or taken off the kidnapping job they’ve been assigned. Jairo’s hallucinations land everyone in a load of trouble, though, and his co-workers stuff him and the ransom money in the trunk of a stolen car to try and get him to safety.

Physically disabled Chabelita is first seen lying in bed with her hands contracted, attempting to turn the pages of a book with a mouthstick that may have been an improvised wooden spoon. She does not appear to have any paid home health care, useful work to do, or even a wheelchair, and her aging parents Juvencio and Anita worry about where the next mortgage payment will come from and who will take care of her when they’re gone without including Chabelita in their discussions. She has no idea they’re down to selling their car to make ends meet one more month, or why their dog is barking madly, or who her parents are talking to so urgently in the next room, or what that mysterious thud was. All we can say is, it’s fate.

Hilary’s Straws

One day, quadriplegic Hilary Lister and her friends smashed up and cannibalized a wheelchair, some metal pipes and a few electric circuit boards. The result was a unique technical invention that allowed her to control a sailboat by breathing into a pair of straws.

Quadriplegic Actor Jim Troesh Dies at 54

From Hollywood Reporter:

Jim Troesh, a screenwriter, actor and entertainment industry disability advocate, died Oct. 1 at St. Joseph Medical Center in Burbank. He was 54.

Troesh was perhaps best known for his three-season role as a quadriplegic attorney on Highway to Heaven, the 1984-89 Michael Landon NBC drama for which he also wrote.

His screenwriting credits also include the 2006 film Color of the Cross, which he penned with Jean-Claude La Marre and Jean Claude Nelson.

As an active member of the WGA West’s Writers with Disabilities Committee, Troesh was the industry’s lone quadriplegic WGAW-SAG dual member and the first quadriplegic to join the actors union. He also served on the Performers Executive Committee of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, was a former national chairman of AFTRA’s Performers with Disabilities Committee and a former president of the Media Access Office.

”What Jim brought to the disability equation was an irreverent, disarming sense of the absurd. Humor kept him going for 41 years,” said WGAW WDC Committee chair Allen Rucker, who dedicated the 2011 Media Access Awards to Troesh at this year’s ceremony held Thursday.

The Media Access Awards honor projects and artists that improve awareness, promote accessibility and champion accurate representations of the disability experience.

Troesh received the prestigious Michael Landon Award from the Media Access Office and was a recipient of the ABC/Disney Writing Scholarship.

Among his recent projects, Troesh created the TV pilot The Hollywood Quad, a sitcom that he wrote, produced, directed and starred in along with guest star Bryan Cranston. Comically chronicling Troesh’s journey in the industry, he turned the program into a podcast series.

Troesh’s other acting credits include Boston Legal, Special Unit, Notes From the Underground, Rise and Walk: The Dennis Byrd Story and Airwolf.

At age 14, Troesh fell off a roof and sustained a spinal injury that left him paralyzed.

A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. on Oct. 21 in North Hollywood at a location to be announced. In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations be made in Troesh’s name to Total Improv Kids — Jim Troesh Scholarship; c/o Linda Fulton; Avery Schreiber Theatre; 11050 Magnolia Blvd., North Hollywood, CA 91601.

A Good Man

On the Documentary Channel at 4 p.m. on July 25:

Chris Rohrlach is not your typical Australian sheep farmer. Willing to try anything to keep wife Rachel out of long-term care, he decides to open a brothel. Nothing has ever stopped Chris and Rachel from doing exactly what they’ve wanted, so outrage from the community doesn’t faze them one bit. A quadriplegic with neurological impairment for all of their 14 married years, Rachel is still Rachel to Chris, and the love of his life. As the camera captures the construction and grand opening of the best little whorehouse in the outback, the film exposes tension between Chris’ indomitable plans to keep his family afloat and Rachel’s own wishes. Reliant on others to translate her eye movements into words, the film creates a novel friction between Rachel’s opaque desires and their secondhand expression. Moving, thought provoking and surprisingly funny.

Guzaarish

Guzaarish (Hindi for “Request”) is the Bollywood remake of “Whose Life is it Anyway?”, and yet another example of the “right to die” disability movie trope.

Guzaarish (Hindi for “Request”) is the Bollywood remake of “Whose Life is it Anyway?”, and yet another example of the “right to die” disability movie trope.

The story centers around Ethan Mascarenhas, once a famous magician, who became a quadriplegic when his best friend betrayed him during a dangerous trick. Ethan has seemingly done well as a quad; he wrote a popular book and appears to have toured to promote it, he’s a Radio Jockey of a popular program called Radio Zindagi, has a romantic if gloomy mansion on a hill, two live-in servants and a nurse, and a sip-and-puff motorized wheelchair. From his home-based studio he exhorts his radio listeners to find beauty in their lives and boasts about his program being the most joyful on the air.

That’s why it’s so surprising when, on his 14th anniversary of becoming a quadriplegic, Ethan suddenly announces that he wants to end it all, and instructs his best friend (a lady lawyer) to file a petition with India’s courts for euthanasia. (Or, as he calls it on his radio program, “Ethanasia”.)

He also suddenly begins snapping at his caregivers and even makes a sexually harassing remark or two to Sophia, his nurse. Disabled viewers probably start wondering if Ethan has some underlying mental health issues at this point.

While it is impossible to deny that many people with disabilities–particularly the newly disabled–are indeed suicidal, “right to die” movies such as Guzaarish are problematic because movies are the primary vehicle for the able-bodied to learn about the lives of the disabled. Suicidal tendencies among the disabled are seen as a perfectly rational, and even noble, response to their condition; a movie such as this only reinforces such perceptions. Depression is thus left untreated and available services unapplied for. Studies show that once disabled people are offered adequate services, pain relief, and adaptive equipment to maximize their independence, they become much less likely to be suicidal.

And indeed Guzaarish bears this out; during the court hearing, it is revealed that Ethan’s mansion is mortgaged to the hilt, and he only has enough savings to cover Sophia’s salary for two more months. Further cracks in Ethan’s cheerful facade begin to appear upon examination. He may have a proper motorized wheelchair, but he only uses it in the beginning of the film. The rest of the time, he’s hauled about slumped in an ill-fitting manual wheelchair. Perhaps his town isn’t particularly wheelchair accessible, nor does he seem to have access to an adapted van or paratransit services. But that doesn’t explain why he hasn’t installed himself on the first floor of his mansion instead of the second, nor added ramps about the extensive grounds. Perhaps he wouldn’t be so depressed if he made an effort to get out more than once in a decade?

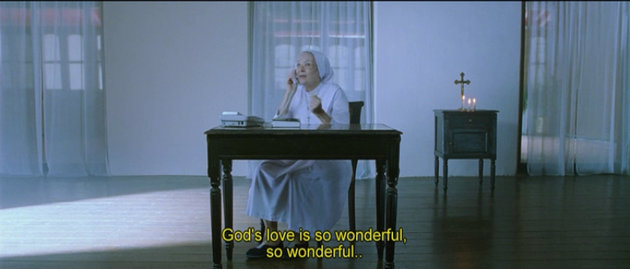

Any quadriplegic viewing the above image is now wondering why Ethan bothered to go through the court system, when the means of offing himself are already at his disposal. Clearly Ethan is crying for help, and those cries are amplified when he puts Ethanasia up for a vote on his radio program after the courts deny his initial petition. Most callers vote no; a handful, including Ethan’s former lover, crushingly vote yes. If Ethan wasn’t depressed before, he surely is now.

A judge decides to hear Ethan’s case, and even moves the courtroom to the foyer of Ethan’s home to accommodate his trouble getting around. Ethan uses showmanship to lock the prosecutor into a trunk, and when he begs for release before a minute is up, Ethan tries to make the point that the prosecutor couldn’t tolerate being confined for even a minute. The judge still denies his request, but Ethan has one more ace up his sleeve: Sophia.

Sophia and Ethan declare their love for each other, and she agrees to marry and then kill him, damn the consequences. They have the most uncomfortable wedding imaginable, with the groom dressed up on his deathbed insulting his guests one by one. Ethan’s doctor friend nearly leaves, but is convinced to stay. All pile on the bed to wish him farewell. If there’s one thing to be grateful for, it’s that Guzaarish narrowly avoids the disability movie cliche of the disabled character dying onscreen.