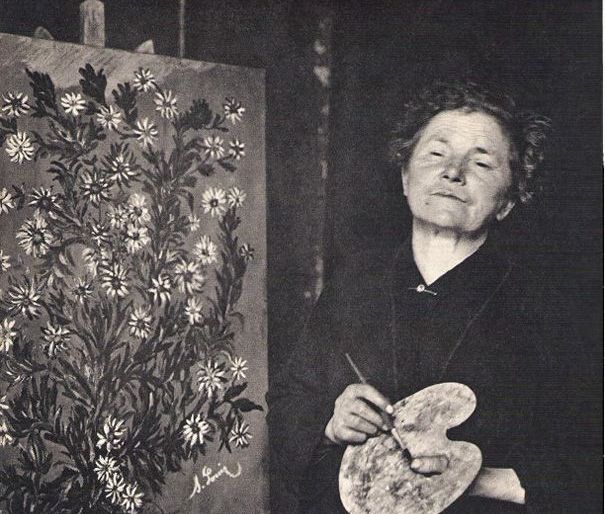

[easyazon-image align=”left” asin=”B0031REQKE” locale=”us” height=”160″ src=”http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/515Iid3xpPL._SL160_.jpg” width=”113″]A portrait of the artist Séraphine de Senlis (born Séraphine Louis), [easyazon-link asin=”B0031REQKE” locale=”us”]Séraphine[/easyazon-link] explores the relationship between her and influential art collector Wilhelm Uhde after their initial meeting in 1912. Aging Séraphine was then working as a maid, subsisting on whatever crumbs her employers left for her and spending any available centime on base white for her paintings. Uhde happens to see some of her early work and buys everything available, enchanted by what he calls her Naive style. (Her employer and community is skeptical, finding her art almost terrifying; it displays the horror vacui characteristic of the art of schizophrenics.) They also manage to find some common ground despite the differences in their ages and socioeconomic classes; Séraphine is perceptive enough to recognize the signs of depression in Uhde, and advises him to spend some time in the woods touching the plants. But her first benefactor must soon leave the country in a hurry, telling Séraphine she must continue to work on her art.

Séraphine already considered this her mandate from heaven, and becomes more and more destitute as the war goes on and the jobs available to her began to dwindle. Certain people are charitable to her over the years, and Uhde finally returns to set her up with an exhibition–“Painters of the Sacred Heart”–and for a time, a regular salary. Séraphine is ill-prepared to handle success and quickly starts living beyond her means, sending Uhde bills for a house and costly wedding dress (though she doesn’t seem to have a groom lined up).

With the Great Depression in full swing, Uhde breaks the news that he’s unable to get her a gallery show or continue buying her paintings. Before she is forced to sell off all her new possessions, though, Séraphine experiences what might be considered a cross between a religious experience, a piece of performance art, and a psychotic break. Clearly taking a page from Lives of the Saints, Séraphine trudges through the streets at dawn dressed in the bridal gown, knocking on each door and leaving silver candlesticks and utensils before the occupants answer. A crowd of women gathers to witness silently, and someone fetches the police. They gently escort her to a waiting van and drive her to a mental asylum typical of the period; inmates in rags and at each other’s throats. Her artistry found no outlet there, and she was cut off from the natural surroundings that helped with her depression.

The film depicts Uhde visiting to observe her from afar and paying for better accommodations (so that she can walk outside and sit under a tree in the final moments of the film), but there’s no evidence he did that in real life. Although Uhde reported that she had died in 1934, some say that Séraphine actually lived until 1942 in a hospital annex at Villers-sous-Erquery, where she died friendless and alone. She was buried in a common grave. Uhde continued to exhibit her work, and today Séraphine Louis’s paintings are exhibited in the Musée Maillol in Paris, the Musée d’art de Senlis, the Musée d’art naïf in Nice, and the Musée d’Art moderne Lille Métropole in Villeneuve-d’Ascq.