Samson & Delilah is set in a remote Aboriginal Community, with the Aboriginal Delilah playing a much more realistic and sympathetic role than her namesake in the Bible.

Samson & Delilah is set in a remote Aboriginal Community, with the Aboriginal Delilah playing a much more realistic and sympathetic role than her namesake in the Bible.

Early in the film, it is shown that an unowned wheelchair is left outdoors, where it serves as an amusing ride for the village urchins, the largest and least promising of whom is age-indeterminate surfer-dude-looking Samson. Samson intimidates a smaller boy into turning over the wheelchair to him, and promptly uses it to play in. He sits outside of the Aboriginal community’s only grocery store in it, begging for handouts; no one is fooled.

Samson is old enough to have sprouted a small mustache and to occasionally amuse himself by playing guitar with some older guys who hang out near the general store. If he has parents, grandparents, or other relations, they don’t seem to be around or overly concerned with his slovenliness and lack of ambition. When he is at his disheveled, dusty home, he huffs glue and/or other inhalants; in one scene where he does some grafitti, he is shown giving a long sniff to the point of the permanent felt-tip pen.

Delilah, by contrast, lives a life of responsibility: she is the primary, if not sole, and most likely unpaid, caregiver for her grandmother Kitty, who is physically disabled and/or frail. Whatever Kitty has is not specified, but Delilah argues with her every morning to take her pills, and is frequently seen pushing her in a standard manual wheelchair (the health care system of that time and place most likely handed out one standard model of wheelchair, regardless of how inappropriate it was to the dusty terrain or their clients’ needs).

Delilah is shown to regularly take Kitty to a spartan corrugated metal chapel containing little more than a large cross, and to appointments at a clinic, at which no wheelchair ramp is seen. Someone (probably Delilah and/or clinic personnel) most likely has to haul Kitty in bodily, separately from her wheelchair. Though Kitty evidently does get to her clinic appointments, the movie does not make it clear exactly how this is accomplished.

Kitty and Delilah make a meager living by selling Kitty’s Aboriginal paintings to a white man who picks them up from them and takes them into town for galler(ies) to sell (at a large markup, Delilah would later discover).

One day while they are out in the yard, Kitty sees Samson just outside their property, and asks who he is. When Delilah tells her, Kitty says they should get married, though Delilah had evidenced no prior romantic interest in Samson (perhaps because she knows Samson as an idler with no visible means of support).

The grandmother’s idea is influenced by the fact that they are the “same skin”. As Americans watching this, the first thought was that like some of our mixed-blood blacks and dubious ancestried whites, some Aboriginals were particular about the color of one’s complexion. As it turns out, what Kitty really had in mind were Aboriginal family systems concerning who was related to whom and proprieties concerning who among these could legitimately marry. This, and several other things, including why the old women of the town beat Delilah bruised and bloody after the death of her grandmother, which were puzzling and left unexplained in the film, are explained in the film’s official FAQ.

Samson’s courting rituals are unmistakable and amusing, as is Delilah’s initial rejection of her putative husband. The two later form a bond after the grandmother dies and the neighborhood biddies beat up Delilah in their quest to find a scapegoat for Kitty’s death. Samson steals the shared community truck and drives the unconscious Delilah as far its tank of gas would take them. He stops only to siphon gas from other vehicles, but uses the soda bottle of gasoline he siphoned for huffing. It never occurs to him to use siphoned gas to refuel the truck when they finally run out of gas. (Though it is never overtly stated, it is implied that Samson has mild brain damage from his inhalant abuse.)

The pair end up sleeping under an overpass, sharing an encampment with an alcoholic homeless older Aboriginal man, who luckily proves friendly to them, albeit in a strange way (among other things, he serves them re-heated, canned spaghetti for breakfast while singing about it). He repeatedly asks the pair to talk to him, to tell him their story, but they remain silent. When he threatens to withdraw his assistance one day, Samson stutters out his name and we realize one of the reasons he doesn’t talk much.

If Delilah’s grandmother wanted her to marry on the theory that in Samson Delilah would have a protector, if not a provider, Samson proves a failure at this too: in one scene, Delilah is abducted by a group of white youths with a car, and Samson almost doesn’t notice while he is walking and huffing gasoline fumes from his soda bottle of siphoned gasoline. (It is only upon her return, with a black eye and most likely raped, that she resorts to huffing. Previously, her “escape” had been listening to music from a car cassette player.) Again the film’s FAQ comes to the rescue: it explains that Samson also has hearing loss and the couple has mostly been communicating through Aboriginal hand signals and body language. This comes into play again when Delilah is similarly hit by a car; Samson is about ten paces ahead and doesn’t notice.

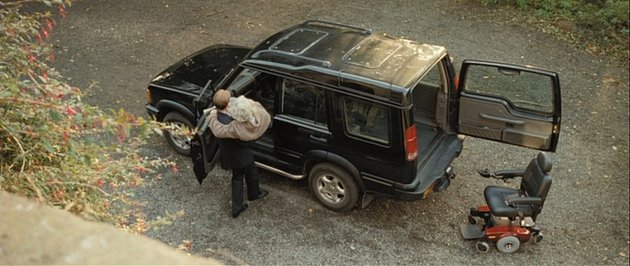

He makes no attempt to retrace his steps and recover her; instead he huffs himself into a weeks-long drug induced stupor. Delilah appears almost as an angel in a clean white hoodie, wearing a shiny leg brace and using a crutch. She’s called in the cavalry; a man from their community picks up the near-dead Samson, carries him to the recovered truck, and drives them both back.

This time, the cadre of old ladies beats Samson with tree limbs, but Delilah fights them off. She cleans up the shack that she and her grandmother called home, burns a painting in tribute, gives Samson a good bath and sets him up in Kitty’s former wheelchair with a radio to keep him entertained. The film ends on a hopeful note; perhaps Samson will recover from the damage he’s done to his brain with the love of a good woman, and for all his faults, perhaps he’ll be a good companion to the scarred Delilah.

Note: though Samson and Delilah has minimal dialogue throughout, only the dialogue in their Aboriginal language is subtitled. English dialogue is not captioned, so deaf and hard-of-hearing folks may have a little trouble following the story. We don’t quite have the heart to stick this movie in the Hall of Shame though.